To help with some of those questions, please take a moment to read the article below. It explains why the steps to ‘social distance’ are being taken. According to researchers, we are following Italy’s curve exactly (about 10-14 days behind them) and we need to flatten the curve!

Be sure to check out the original article at https://www.forbes.com/sites/tarahaelle/2020/03/13/why-everything-is-closing-for-coronavirus-its-called-flattening-the-curve/#6ac1e0a46e2b

EDITORS' PICK|1,331,256 views|04:18am EST

Why Everything Is Closing For Coronavirus:

It’s Called ‘Flattening The Curve’

When organizers cancelled SXSW—the huge music/film/tech/education festival-conference that brings hundreds of thousands of visitors to Austin, Texas every March—it was only a matter of time before the other dominoes began falling.

As of this writing, the NBA, NHL and Major League Soccer have suspended play, MLB has pushed back the season start, the NCAA cancelled March Madness, several universities have cancelled spring football games, the PGA Tour cancelled the Players Championship, and the future of the 2020 Summer Olympics is in doubt. And that’s just sports.

School districts from Seattle to Baltimore—including the entire states of Maryland, Michigan and Ohio—have closed schools, and more than 100 colleges and universities have cancelled all in-person classes and moved online. The huge music festival Coachella has been postponed, along with a long list of concerts and music tours, the video game industry’s largest trade show and all Broadway shows through April 12. Movie theaters may be next.

Even Walt Disney World and Disneyland—in fact, all Disney parks—have closed their gates. For Disneyland, it’s only the park’s third closure in its history, following JFK’s assassination and 9/11.

The economic implications of all these closures are incalculably high—SXSW means a loss of more than $350 million, including thousands of low-income workers’ lost tips and wages, and that won’t hold a candle to the losses from professional sports and theme park cancellations. So the decision to suspend seasons, cancel events and close up shop are not being made lightly.

And yet… there have only been about 1,660 cases of COVID-19 diagnosed, and fewer than 50 deaths. As you’ve probably heard too many times by now, every year the flu sickens millions—nearly 50 million this year—and kills tens of thousands, perhaps as many as 52,000 this season alone.

What gives? Why so many extraordinary cancellations, whose costs will tally into the billions, for so few cases?

There’s a good reason to “cancel everything.” All these decisions by public officials and businesses are aimed at one goal: slowing down the spread of the virus to avoid overburdening a healthcare system that doesn’t have the infrastructure to handle a sudden surge of tens of thousands of cases at once. Without mass closings, that surge is exactly what will happen, just as it has in Italy.

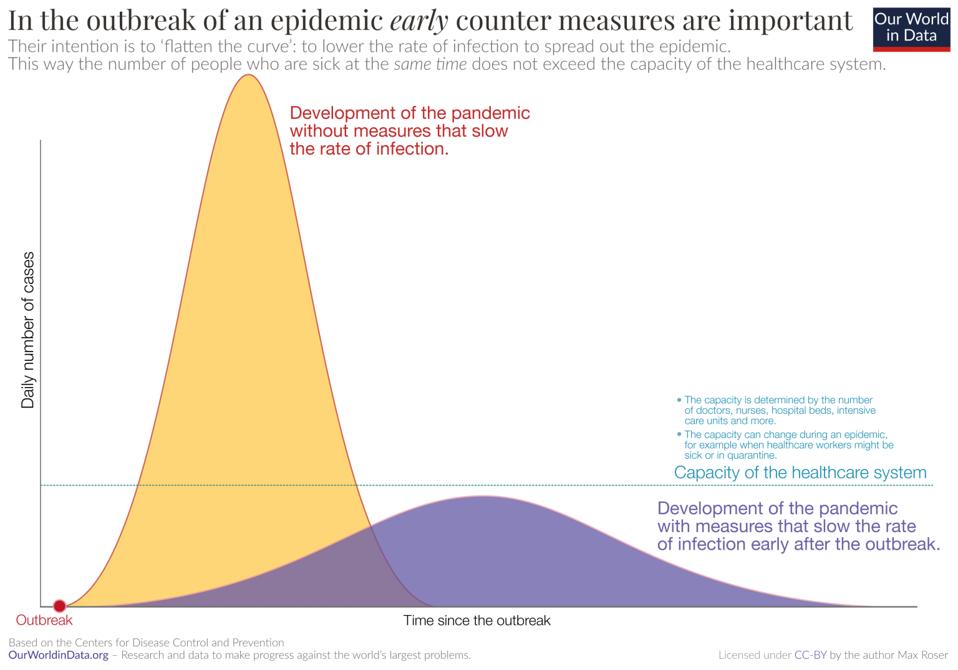

It’s called “flattening the curve.” And that’s exactly what it is when you see it visually. Here’s what is looks like in an illustration from Max Roser at Our World in Data, very similar to the figure in a recent Emerging Infectious Diseases study on social distancing to reduce pandemic influenza.

Basically, if you assume a certain number of cases are inevitably going to occur—which epidemiologists can somewhat predict based on how the disease is behaving—continuing business-as-usual allows cases to escalate rapidly in just a few weeks, spiking so high at once that they completely overwhelm hospitals. In such a scenario—such as Italy is facing now—more deaths are likely because there simply aren’t enough hospital beds, enough face masks, enough IV bags, even enough healthy doctors and nurses to care for everyone at once.

But if that same number of cases can be stretched out over months, never quite exceeding the healthcare system’s capacity, then people will get the care they need, more healthcare providers can avoid illness and burnout, and fewer people are likely to die—as South Korea has impressively shown.

But are we really headed for that many cases?

Yes.

As former FDA commissioner Scott Gottlieb explained in an excellent Q&A a few days ago, the novel coronavirus—just declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization—is beyond containment. If it’s not already in your community, it’s coming soon. The only reason total US cases aren’t already skyrocketing is that coronavirus testing has been such a mess that too few people—just 77 by the CDC this whole week—are being tested. You can’t count cases you haven’t identified yet.

But every indication is that the US is on track to see the same exponential increase other countries are seeing, as scientist Mark Handley has been tracking on Twitter.

Meanwhile, as Aaron Carroll, MD—the guy who usually doesn’t worry—pointed out in the New York Times yesterday, the US has only about 2.8 hospital beds per 1,000 people—less than the 3.2 in Italy and 4.3 in China. (South Korea outperforms everyone with 12.3 hospital beds per 1,000 people.) And that’s total hospital beds, not the ones reserved for the sickest patients.

“It’s estimated that we have about 45,000 intensive care unit beds in the United States,” Carroll writes. “In a moderate outbreak, about 200,000 Americans would need one.”

So what do we do to avert disaster? We have to flatten the curve. Fortunately, people are listening. The idea has caught on so well among armchair epidemiologists that the #flatteningthecurve and #FlattenTheCurve hashtags have trended several times on Twitter in recent days.

Clearly, public officials and businesses are heeding the warnings of public health officials, as evidenced by all the closings and cancellations. But to be effective, ordinary people need to do their part by avoiding as much as possible any crowds and places where large numbers of people congregate, such as movie theaters, malls and events that haven’t been cancelled.

After Italy shut down, The Atlantic recently asked “Which Country Will Be Next?” If Americans don’t flatten that curve, it will be us.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.